April 17, 2025

Initial Archive Design Displayed in A 360 Degree Screen Room

About the Archive

Heya ‘95 - ‘25: The Games of My Life is a personal archive of the digital games I’ve played over the course of three decades of my life. The archive is structured through multiple lenses. First, it arranges the games chronologically, mapping them alongside major life events–starting elementary school, immigrating to the U.S. at the age of 10, or receiving my first gaming console. Second, the games are grouped by their social function: whether they fostered connection or solitude, competition or collaboration. Lastly, they are organized by the motivations behind my play: whether I was driven by pure curiosity, need for expression, desire to connect, or drive to escape. (Of course, one game might appear in multiple places—it might have been both a source of connection and a form of escape.)

Description

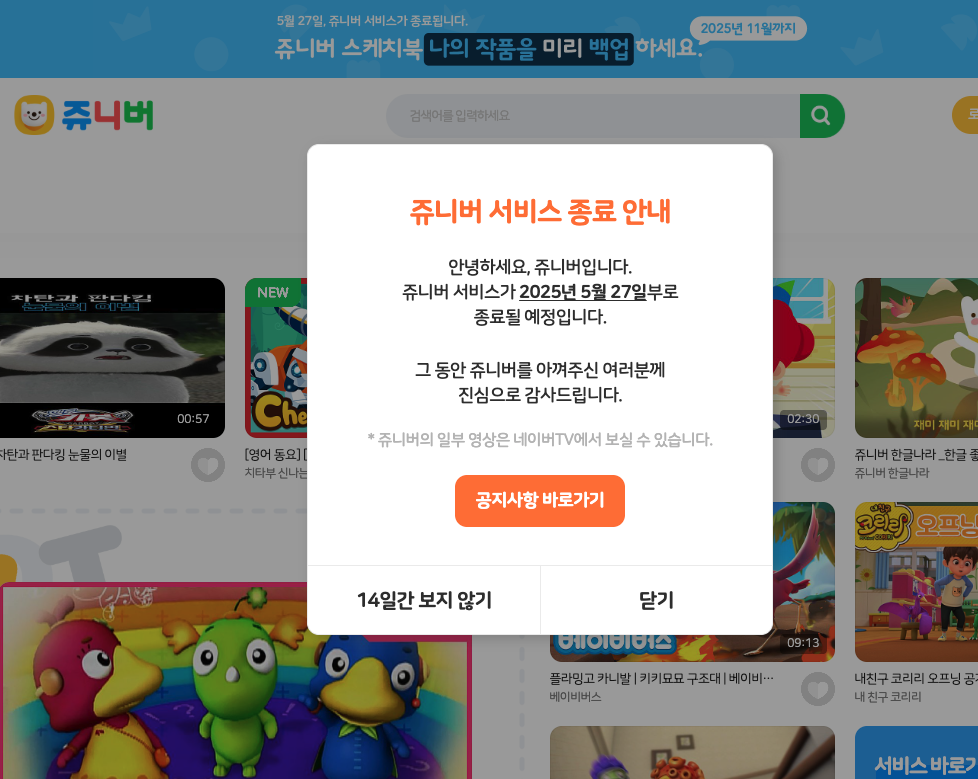

I recently learned that Junior Naver (쥬니어 네이버 or 쥬니버), a Korean portal site for children best remembered from its flash games, is shutting down on May 27th, 2025. Although I hadn’t visited the site since I was a tiny kid, the news still struck me with melancholy. It felt as if a beloved playground from my hometown was shutting down–or even, as if an entire neighborhood I used to hang around was being erased from a map.

In response, I revisited Shu’s Getting Ready (슈의 외출준비), one of the games I used to play on that site, for the first time in twenty years. That brief moment of play gave me an interesting feeling: a sense of time collapsing. Suddenly, I was once again a child, awkward and curious, snuck behind a bulky Samsung computer in Korea. At the same time, I was still a grown-up, clicking away at my thin and sleek Macbook Pro in Finland.

I finished the game and closed my laptop, but I was left with a question: Why does my body react so strongly to places that do not exist physically? Why do virtual spaces stir such visceral nostalgia? In search of an answer, I began to remember. I started to list out all the games I had played throughout my life. I even interviewed my father and brother and combed through numerous Korean blogs to fill in the holes in my memories. At the end of my research, I was left with surprises. The process didn’t just bring back lost memories; it helped me understand my current self better.

(1) A screenshot of Junior Naver; the modal announces that the site will close on May 27th 2025

(2) A screenshot of Shu's Getting Ready (슈의 외출준비) Game

Looking Back

In remembering the games, I remembered myself. Some fragments of my life that had slipped away resurfaced in the process. For instance, I had completely forgotten that my brother and I lived with our grandma from my birth until I turned 5, as both of our parents had to work. It was grandma’s house where a clunky computer existed and the first gameplays of my life happened. My earliest memories in life came back to me as well: watching my brother play Sonic the Hedgehog (1995) and Disney's Action Game: Tarzan (1999), around the same time I rebelliously peed on my grandma’s carpet to piss her off (no pun intended). When my brother felt generous, I was even given a chance to play myself. This meant that I was playing games as early as I was four years old. (All this time I was worried about kids growing up with iPads, but who am I to talk?).

Even after leaving our grandma’s house, games stayed in my life. Especially because digital games were a dominant culture–I’d even say a national hobby–in Korea starting from the mid-1990s. After school, I would play computer games in PC bangs (internet cafés) or mobile games on buses on the way to hakwons (학원), Korea’s ubiquitous afterschool academies. And as the internet grew, I started to play more online games where I was talking to strangers online. Even when I eventually left Korea for the U.S., I continued to play. In fact, as I was surrounded by a foreign language and unfamiliar terrains, games became a stable ground for me that I can always return to.

I used to view games as something separate from reality–a place to escape to from the real world. But building this archive has shown me otherwise: games are not departures from the real but are interesting extensions of it. In fact, they are places where I could safely experiment with different parts of myself–trying on new roles, personalities, even gender expressions. In other words, they were not merely where I went to escape but also where I wanted to be. And in revisiting the games, I realized they didn’t just reflect who I was; they also shaped who I became.

Note on Games’ Limitations

Interestingly, some memories of games were shaped by the absence of play. For example, I often watched my brother and his friends play Starcraft, a military sci-fi strategy game, but I was never invited to play. It was considered a “boy’s game”. I would often sit nearby, waiting for their rounds to end and sometimes even cheering them on. I never got to touch the keyboard, but I absorbed the sounds and the rhythm of their matches–they got stored in my body as they randomly come back to me even to this day. This made me realize that there is more to games than players; games can involve spectatorship and sometimes even exclusion.

For all their creative and connective power, digital games also carry limitations. They can reinforce social hierarchies, encourage addictive behavior, and reflect exploitative labor systems within the game development industry. My own exclusion from “boy’s games” reminds me that access is (or at least was) often gendered in Korea. Scholars like Alexander Galloway have shown how games are not neutral; they express ideology, enforce rules, and encode assumptions about who belongs and how play is meant to unfold. To archive games, then, is also to examine what and who is left out as well. In this way, remembering becomes an act not only of nostalgia, but also of critique.

Looking Ahead

I get a feeling that this archive is just beginning. I’m especially keen on expanding it to include experiences outside of my own. What other insights might emerge if I traced my gaming memories alongside those of others–across generations, geographies, and languages? By placing these journeys side by side, we will start to see an archive of games not just as personal history but as a shared cultural language. This is because, I would argue, digital games are inherently social. Their digital nature allows the same virtual world to be accessed by people separated by time, place, and purpose.

To this day, digital games continue to evolve. Their graphics are advancing, online networks are growing, and technologies like VR are getting more immersive. With such advancement, the boundaries between “virtual” and “physical” life become more porous. And it is becoming increasingly clear that games are not simply media we consume, but environments we co-author. As platforms like Minecraft and Roblox reveal, games are no longer only designed worlds—they can also be worlds we build ourselves, often together. If I were to use Stuart Hall’s concepts, I would say that a digital game is a media where the weight can be heavily shifted from the media creator’s encoding process to the audience's decoding process.

Games are not separate from life; they are one of its many terrains. That’s why I see this archival practice not merely as personal reflection but also as meaningful cultural work. It is a way of recognizing digital play as part of our lived history, no less meaningful than places we’ve lived in as kids. By mapping not only what I played but when, how, with whom, and why, I begin to see patterns that extend beyond my own life. These are patterns that speak to a generation’s or a culture’s way of relating to technology, to other humans, and to the world. In this way, to archive games is to archive the shifting terrain of society itself.